Navigating the vast landscape of antibiotics can feel like deciphering an ancient medical scroll, especially when you start comparing drug classes and their subtle but crucial differences. When it comes to the cephalosporin family, a cornerstone of antibacterial therapy for decades, understanding the nuances between generations is paramount for effective treatment. This article delves into the comparison of 2nd generation cephalosporins to other generations, exploring their unique strengths, limitations, and the specific clinical scenarios where they truly shine or fall short.

We're going to break down why these drugs were developed, what infections they target best, and how they stack up against their siblings in the cephalosporin lineage. Think of this as your expert guide to making informed decisions in a complex medical world.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways on Cephalosporin Generations

- Cephalosporins are broad-spectrum, bactericidal antibiotics that inhibit bacterial cell wall synthesis. There are five distinct generations.

- First Generation (e.g., cephalexin, cefazolin) primarily targets Gram-positive bacteria, with moderate Gram-negative activity. Great for skin/soft tissue infections and surgical prophylaxis.

- Second Generation (e.g., cefuroxime, cefoxitin) represents a bridge. It offers increased activity against certain Gram-negative bacteria (like H. influenzae and Neisseria) compared to first-gen, while retaining some Gram-positive coverage. A unique subgroup (cephamycins like cefoxitin) also covers anaerobes.

- Third Generation (e.g., ceftriaxone, ceftazidime) generally boasts stronger and broader Gram-negative coverage than second-gen, including some highly resistant strains, but often has reduced Gram-positive efficacy. Many can cross the blood-brain barrier.

- Fourth Generation (e.g., cefepime) offers a broad spectrum, combining the Gram-positive activity of first-gen with the extensive Gram-negative coverage of third-gen, including anti-Pseudomonal action.

- Fifth Generation (e.g., ceftaroline) provides a unique advantage: activity against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), addressing a critical gap left by earlier generations.

- Clinical Choices depend on the suspected pathogen, local resistance patterns, patient history, and the specific site of infection. No single generation is superior; rather, each has its niche.

The Cephalosporin Family Tree: A Quick Primer on How They Work

Before we get into the specifics of the generations, let's briefly touch on what cephalosporins are and how they operate. These remarkable antibiotics are derived from the mold Acremonium (formerly Cephalosporium) and belong to the beta-lactam class, much like penicillins. Their core mechanism is elegant in its destructive simplicity: they interfere with bacterial cell wall synthesis.

Specifically, cephalosporins bind to crucial enzymes called penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which are responsible for cross-linking peptidoglycan units – the building blocks of the bacterial cell wall. By blocking this critical step, they compromise the integrity of the cell wall, leading to lysis (rupture) and ultimately, the death of the bacterial cell. This makes them bactericidal, meaning they actively kill bacteria rather than just inhibiting their growth. The evolution through five generations reflects a continuous effort to expand their spectrum of activity, improve their potency, and overcome emerging bacterial resistance.

Spotlight on 2nd Generation Cephalosporins: What Makes Them Tick?

The 2nd generation cephalosporins carved out their own significant space in the antibiotic arsenal, acting as a crucial bridge between the primarily Gram-positive focused first generation and the heavily Gram-negative oriented third generation. Developed as the second wave of these antibiotics, they were designed to address some of the limitations of their predecessors. For a more in-depth look at this specific class, you might find our guide on Understanding second-generation cephalosporins incredibly useful.

Expanded Gram-Negative Reach

Compared to first-generation cephalosporins, these drugs demonstrate a noticeably increased activity against a broader range of Gram-negative bacteria. This includes important pathogens like Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae (specifically non-penicillinase producing strains), Klebsiella species, and Escherichia coli. This expanded coverage made them valuable tools for treating respiratory and urinary tract infections where these organisms are often culprits.

Maintaining Some Gram-Positive Ground

While bolstering their Gram-negative capabilities, 2nd generation cephalosporins didn't completely abandon their roots. They still retain activity against a good selection of Gram-positive aerobes, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin-susceptible strains), S. epidermidis, and S. pyrogenes. This makes them versatile enough to handle infections where both Gram-positive and Gram-negative involvement is suspected. However, their Gram-positive prowess is generally less than that of the 1st generation.

The Anaerobic Advantage: Cephamycin Subgroup

A unique feature of the 2nd generation is its division into subgroups. One of these, the "cephamycin" subgroup (which includes drugs like cefoxitin and cefotetan), is particularly noteworthy for its increased coverage against Bacteroides species. This anaerobic activity is a significant clinical advantage, making them suitable choices for mixed aerobic-anaerobic infections, particularly in the abdominal and gynecological realms. The "cefuroxime-like" subgroup, on the other hand, is recognized for its enhanced coverage against H. influenzae.

Notable Members of the 2nd Generation

Common examples you might encounter include:

- Cefaclor

- Cefotetan (often known by brand name Cefotan)

- Cefoxitin

- Cefprozil (often known by brand name Cefzil)

- Cefuroxime (known by brand names Ceftin, Zinacef)

It's important to note that while versatile, most strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter species are typically resistant to 2nd generation cephalosporins. This is a critical distinction when facing severe nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections where these formidable pathogens are often involved.

First Generation: The Foundation (and How 2nd Gen Builds On It)

To truly appreciate the 2nd generation, we need to understand its predecessor. First-generation cephalosporins, like cefazolin (IV) and cephalexin (oral), were the pioneers. They are characterized by excellent activity against Gram-positive bacteria, particularly Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) and Streptococcus pyogenes. Their Gram-negative coverage is more limited, generally encompassing E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis.

Where 1st Gen Shines: They are often the go-to for skin and soft tissue infections (cellulitis, impetigo), uncomplicated urinary tract infections, and are extensively used for surgical prophylaxis (preventing infections after surgery) due to their reliable Gram-positive coverage.

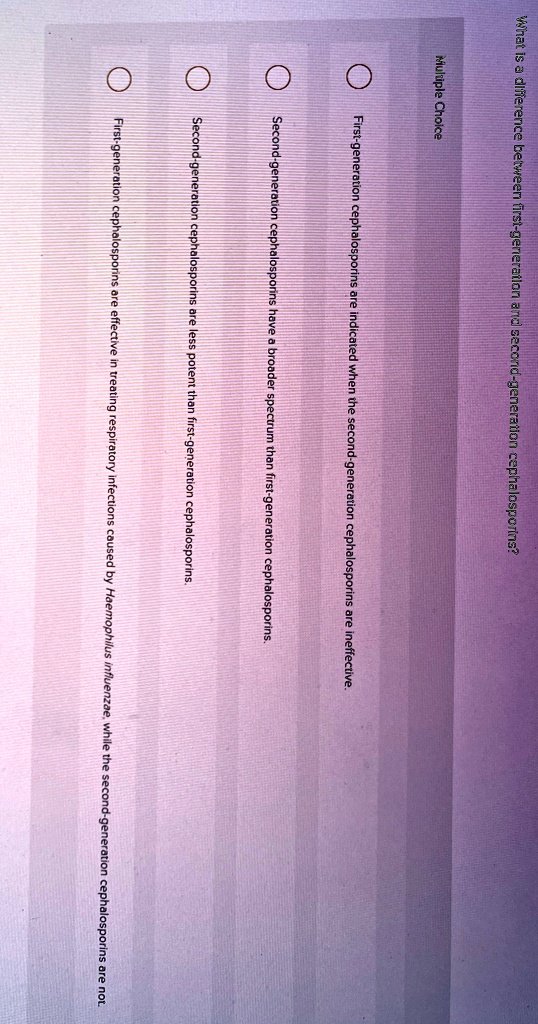

How 2nd Gen Improved: The leap to the 2nd generation was primarily about bolstering Gram-negative activity. While 1st gens were good for common Gram-positive skin infections, they weren't as effective against respiratory pathogens like H. influenzae or some of the more challenging Enterobacteriaceae. The 2nd generation filled this gap, offering a broader reach that positioned them for treating a wider array of infections, including certain lower respiratory tract infections, that 1st gens might miss. They also introduced the crucial anaerobic coverage with the cephamycins, a capability largely absent in the 1st generation.

Second Generation vs. Third Generation: A Shifting Spectrum

The transition from 2nd to 3rd generation cephalosporins marks a significant shift in the balance of antibacterial power. This is where the trade-offs become more apparent.

Third Gen's Leap in Gram-Negative Efficacy

Third-generation cephalosporins (e.g., ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime) were developed to deliver even more potent and broader activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Many of them can tackle a wider range of enteric Gram-negative bacilli and are often effective against multi-drug resistant strains that might overwhelm a 2nd generation agent. For instance, ceftazidime is notable for its specific activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a pathogen resistant to earlier generations. Many 3rd generation cephalosporins also have the ability to penetrate the central nervous system, making them invaluable for treating meningitis.

Reduced Gram-Positive Activity

However, this enhanced Gram-negative firepower often comes at a cost: a reduction in Gram-positive activity compared to the 1st and 2nd generations. While they generally remain active against streptococci, their efficacy against staphylococci, especially MSSA, is typically diminished.

When to Choose 2nd vs. 3rd

- Choose 2nd Generation when: You need good Gram-positive coverage (though less than 1st gen), increased Gram-negative coverage (especially H. influenzae), and potentially anaerobic coverage (cephamycins) for conditions like community-acquired pneumonia, sinusitis, otitis media, or certain intra-abdominal and gynecological infections. They offer a good balance when the pathogen isn't definitively known but likely falls within their spectrum.

- Choose 3rd Generation when: You're dealing with more severe Gram-negative infections, hospital-acquired infections, meningitis, sepsis, or infections where Pseudomonas is suspected. Their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier for CNS infections is a key differentiator. They are often reserved for more serious conditions or when resistance to narrower-spectrum agents is a concern, to help preserve their efficacy.

This comparison highlights that each generation has been optimized for different infectious challenges. Using a 3rd gen when a 2nd gen would suffice can contribute to unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use, potentially driving resistance.

Beyond Second Generation: The Rise of 4th and 5th Gens

The continuing evolution of cephalosporins was driven by the relentless challenge of bacterial resistance. The 4th and 5th generations represent further refinements to tackle increasingly difficult pathogens.

Fourth Generation: The Broad-Spectrum Powerhouse

Fourth-generation cephalosporins, like cefepime, are often described as having the best of both worlds. They combine the excellent Gram-positive coverage reminiscent of the 1st and 2nd generations with the potent, broad Gram-negative activity of many 3rd generation agents, crucially including anti-Pseudomonal activity. This makes them exceptionally broad-spectrum, often reserved for empiric treatment of severe hospital-acquired infections, febrile neutropenia, and complicated intra-abdominal infections where multiple resistant organisms are a concern. They are a significant step up when facing critical, life-threatening infections.

Fifth Generation: Targeting MRSA

The latest entrants, fifth-generation cephalosporins such as ceftaroline (Teflaro), address one of the most pressing antibiotic resistance challenges: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Previous generations largely lacked reliable activity against MRSA. Ceftaroline specifically binds to an altered PBP (PBP2a) in MRSA, allowing it to disrupt cell wall synthesis effectively. This unique capability makes them invaluable for treating serious skin and soft tissue infections, as well as community-acquired bacterial pneumonia caused by MRSA.

Why 2nd Gen Still Holds Its Ground

Despite the advancements of 4th and 5th generations, 2nd generation cephalosporins remain highly relevant. They offer a more targeted approach for specific infections where their spectrum is sufficient. Using a 4th or 5th generation drug when a 2nd generation would work is an example of antibiotic overuse, contributing to the development of resistance. The principle of "right drug, right bug" ensures that these valuable, broader-spectrum agents are preserved for when they are truly needed. For many common community-acquired infections, the balanced spectrum of a 2nd gen cephalosporin remains an excellent and appropriate choice.

Clinical Scenarios: Where 2nd-Gen Cephalosporins Shine (and Where They Don't)

Understanding the microbiological profile of 2nd generation cephalosporins allows us to pinpoint their optimal clinical applications. They're generally safe with low toxicity and good efficacy when prescribed appropriately.

Where They Excel:

- Lower Respiratory Tract Infections (LRTIs): For community-acquired pneumonia, acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, and sinusitis, especially when H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae, or M. catarrhalis are suspected. Cefuroxime is a common choice here.

- Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: While 1st gens are often preferred for uncomplicated cases, 2nd gens can be useful for more complex infections, particularly those with a polymicrobial component or where H. influenzae or anaerobes might be involved.

- Intra-abdominal Infections: The cephamycins (e.g., cefoxitin, cefotetan) are particularly valuable here due to their excellent anaerobic coverage against Bacteroides species, which are common in abdominal abscesses, diverticulitis, and peritonitis.

- Gynecological Infections: Similarly, their anaerobic activity makes cephamycins suitable for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or other gynecological infections caused by mixed flora.

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): For more serious or complicated UTIs, especially those involving E. coli or Klebsiella that might be resistant to narrower agents, a 2nd gen cephalosporin can be effective.

- Bone and Joint Infections: They can be considered for specific bone and joint infections caused by susceptible strains, though often 1st or 3rd gens are more common depending on the pathogen.

- Meningitis in Children: Some 2nd generation cephalosporins, like cefuroxime, can achieve therapeutic levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and may be used for bacterial meningitis in children caused by susceptible organisms, such as H. influenzae.

- Blood Infections (Bacteremia): When caused by susceptible Gram-positive or Gram-negative organisms, 2nd gen cephalosporins can be part of the treatment regimen.

Where They Are Not First Choice (and Why):

It's crucial to remember that cephalosporins, including the 2nd generation, are generally not first-choice antibiotics in many scenarios. They are often reserved for use when other, narrower-spectrum, and potentially less costly antibiotics (frequently penicillins) cannot be used due to allergy, resistance, or specific patient factors. For instance, for an uncomplicated strep throat, penicillin or amoxicillin would be the primary choice.

Key Resistance Concerns: Most strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter species are resistant to 2nd generation cephalosporins, requiring the use of 3rd, 4th, or even 5th generation cephalosporins, or other antibiotic classes entirely. Similarly, MRSA infections will not respond to 2nd generation cephalosporins.

Navigating the Risks: Safety and Side Effects of 2nd Gen

Like all medications, 2nd generation cephalosporins come with potential side effects, though they are generally considered safe with low toxicity. Understanding these can help patients and clinicians manage expectations and recognize when to seek further medical attention.

Common, Mild Side Effects:

Most minor side effects occur once therapy begins and often resolve within 1 to 2 days as the body adjusts. These can include:

- Abdominal pain or stomach discomfort

- Nausea and vomiting

- Decreased appetite

- Diarrhea (a very common antibiotic side effect)

- Dizziness

- Skin rash (often mild and transient)

- Difficulty in breathing (mild, not allergic in nature)

- Low blood pressure (usually transient)

- Fever (often drug-induced)

- Yeast infections (oral thrush, vaginal yeast infections) due to disruption of normal flora

Transient increases in liver enzymes have also been reported, usually without significant clinical impact, resolving after discontinuation of the drug.

Serious Side Effects and Important Warnings:

While rare, it's vital to be aware of potentially serious adverse events:

- Allergic Reactions: This is the most significant concern. Reactions can range from mild skin rashes and hives to severe swelling (angioedema) and, rarely, life-threatening anaphylaxis.

- Penicillin Cross-Allergy: Up to 10% of individuals with a history of penicillin allergy may also be allergic to cephalosporins. This is a critical consideration for prescribers. While the risk is lower with newer cephalosporins, caution is always advised.

- Drug-Induced Hemolytic Anemia: Though uncommon, this condition, where red blood cells are destroyed by the immune system in response to the drug, has been associated with cephalosporin use.

- Super-infections: Like other broad-spectrum antibiotics, 2nd generation cephalosporins can disrupt the normal gut microbiome, leading to overgrowth of opportunistic pathogens. The most serious example is Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), which can cause severe diarrhea, pseudomembranous colitis, and can be life-threatening.

- Seizures: Rarely, seizures have been reported, with the greatest risk occurring in patients with pre-existing kidney disease, as impaired renal function can lead to higher drug concentrations. Dosage adjustments are crucial in these patients.

Patients should always inform their healthcare provider of any known allergies, especially to penicillins or other antibiotics, and report any unusual or severe symptoms during treatment.

Making the Call: Decision Criteria for Prescribers (and Informed Patients)

Selecting the right antibiotic is a complex decision that involves weighing multiple factors. For 2nd generation cephalosporins, the decision-making process typically considers the following:

- Patient History and Allergies: A detailed allergy history is paramount. Any history of penicillin allergy, particularly severe reactions like anaphylaxis, requires careful consideration due to the potential for cross-reactivity.

- Type and Severity of Infection: Is it a skin infection, a respiratory tract infection, or an intra-abdominal abscess? The suspected site of infection helps narrow down the likely pathogens. Is it a mild, moderate, or severe infection? For severe, life-threatening infections, a broader-spectrum agent might be chosen empirically while awaiting culture results.

- Suspected Pathogen(s): Based on the clinical presentation, common etiologies for the specific infection, and local epidemiology, what bacteria are most likely causing the infection? For instance, if H. influenzae is highly suspected in an LRTI, a 2nd gen like cefuroxime is a strong contender. If MRSA is a possibility, a 5th gen would be required, or another class entirely.

- Local Resistance Patterns (Antibiogram): This is a critical piece of information. What are the common resistance rates for various bacteria in your geographic area or specific hospital? A pathogen that might typically be susceptible to a 2nd gen cephalosporin could be resistant in certain regions, necessitating a different choice.

- Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics: Does the antibiotic reach the site of infection in sufficient concentrations? For example, some cephalosporins penetrate the central nervous system better than others, making them suitable for meningitis.

- Patient-Specific Factors: This includes renal or hepatic function (as dosage adjustments may be needed), age, pregnancy status, and concurrent medications that might interact.

- Cost and Availability: While clinical efficacy is primary, the cost and availability of an antibiotic can also be a practical consideration, especially in outpatient settings or resource-limited environments.

- Antibiotic Stewardship: Increasingly, clinicians are guided by principles of antibiotic stewardship, aiming to use the narrowest effective spectrum antibiotic for the shortest effective duration to minimize resistance development. This often means preferring a 2nd gen over a 3rd or 4th gen if it's clinically appropriate.

Ultimately, the choice of a 2nd generation cephalosporin reflects a thoughtful balance, often leveraging their expanded Gram-negative and (for cephamycins) anaerobic coverage while still maintaining reasonable Gram-positive activity, positioning them as a versatile option for many common infections where narrower agents might not suffice, but ultra-broad-spectrum drugs are not yet warranted.

Common Questions About Cephalosporin Generations, Answered

Let's tackle some frequently asked questions that clarify the role and relevance of 2nd generation cephalosporins.

Are 2nd generation cephalosporins still relevant in modern medicine?

Absolutely. Despite the emergence of newer generations, 2nd generation cephalosporins remain highly relevant. They offer a balanced spectrum for many common community-acquired infections, particularly those involving respiratory pathogens like H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae, as well as intra-abdominal and gynecological infections requiring anaerobic coverage. Their use in appropriate scenarios helps preserve broader-spectrum antibiotics for more resistant or severe cases, which is crucial for combating antibiotic resistance.

What's the main advantage of 2nd gen over 1st gen?

The primary advantage of 2nd generation cephalosporins over 1st generation is their significantly increased activity against certain Gram-negative bacteria, notably Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and enhanced activity against some Enterobacteriaceae. Additionally, the cephamycin subgroup of 2nd gens provides important anaerobic coverage (against Bacteroides species), which is largely absent in 1st generation agents. This broader reach makes them suitable for a wider range of infections, particularly in respiratory and abdominal sites.

Why wouldn't I just use a 3rd gen for everything, since they're often broader?

Using a 3rd generation cephalosporin for every infection, even those that could be effectively treated by a 2nd generation, is generally discouraged due to principles of antibiotic stewardship. While 3rd gens often have broader Gram-negative coverage, they typically have reduced Gram-positive activity compared to 1st and 2nd gens. More importantly, indiscriminate use of broader-spectrum antibiotics contributes significantly to the development of antibiotic resistance. Reserving 3rd (and higher) generation cephalosporins for when they are truly necessary helps maintain their efficacy for severe, resistant infections where they are indispensable.

Can I take a 2nd gen if I'm allergic to penicillin?

This is a nuanced question. While a history of penicillin allergy does increase the risk of an allergic reaction to cephalosporins (known as cross-reactivity), this risk is generally low, estimated at around 1-10%, and is significantly lower for 2nd and later generations compared to 1st generation cephalosporins. The risk is highest when the side chains of the penicillin and cephalosporin are structurally similar.

However, it's crucial to consult with your healthcare provider. If you have a mild, non-anaphylactic penicillin allergy, a 2nd generation cephalosporin might be prescribed with careful monitoring. If you have a severe, anaphylactic penicillin allergy, your doctor will likely opt for an antibiotic from a completely different class to avoid any risk. Always disclose your full allergy history to your doctor.

The Future of Antibiotics: Why Understanding Generations Matters

The battle against bacterial infections is a continuous arms race. As bacteria evolve and develop resistance, the pharmaceutical industry strives to create new and improved antibiotics. The generational progression of cephalosporins perfectly illustrates this ongoing effort: each new generation was designed to overcome the limitations of its predecessors, expanding the spectrum of activity and improving efficacy against increasingly challenging pathogens.

Yet, with great power comes great responsibility. The very existence of multiple generations underscores the importance of choosing the right antibiotic for the right infection. Overusing broad-spectrum agents when a narrower-spectrum drug would suffice accelerates resistance, eroding the effectiveness of our most critical antibiotics. The 2nd generation cephalosporins, with their balanced profile of Gram-positive, enhanced Gram-negative, and in some cases, anaerobic coverage, play a vital role in this delicate ecosystem. They are often the sensible choice, offering effective treatment without unnecessarily escalating the resistance threat.

For both healthcare professionals and informed patients, a clear understanding of these generational differences isn't just academic—it's foundational to preserving the efficacy of these life-saving drugs for generations to come. By appreciating the unique strengths and limitations of each class, we can all contribute to more responsible antibiotic use and better health outcomes.