When you take medication, it's not a simple one-and-done process. The journey a drug takes through your body – from the moment you swallow a pill to when it’s finally eliminated – profoundly influences whether it helps or harms you. This intricate dance, governed by Dosing, Administration, and Pharmacokinetics, is the silent force optimizing drug treatment for patients around the globe. Understanding this journey isn't just for pharmacologists; it's a vital piece of the puzzle for anyone wanting to truly grasp how medicines work and why precise healthcare is so critical.

At a Glance: Decoding Your Medication's Journey

- Pharmacokinetics (PK) explains what your body does to a drug, broken down into four key stages: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME).

- Absorption is how the drug gets into your bloodstream. How fast and how much gets in depends on the drug's properties, your body's conditions (like stomach pH), and its formulation.

- Distribution is where the drug travels within your body to reach its target. Some drugs stay mostly in the blood, others spread widely into tissues.

- Metabolism (often in the liver) chemically changes the drug, usually to make it easier to get rid of. This can activate prodrugs or create toxic byproducts.

- Excretion is how your body gets rid of the drug and its metabolites, primarily via kidneys (urine) or liver (bile).

- Dosing and Administration are carefully chosen based on PK principles to achieve the right drug concentration in your body, keeping you safe and effective.

- Factors like age, disease, and genetics can significantly alter a drug's ADME profile, requiring personalized dosing adjustments.

The Body's Interaction with Drugs: An ADME Story

Pharmacokinetics is the branch of science that maps out the entire voyage of a drug within your system. Think of it as the body's interaction with the drug, not the drug's effect on the body (that's pharmacodynamics). This journey is neatly summarized by the acronym ADME: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion. These four steps dictate how quickly a drug starts working, how strong its effect will be, and how long it will last. Mastering these processes is paramount for clinicians to fine-tune dosages and minimize unwanted side effects.

Nearly every medication you take undergoes these ADME processes to some degree. Factors like how easily a drug dissolves in fat (lipid solubility), its size (molecular weight), whether it binds to proteins in your blood, and how susceptible it is to your body's enzymes all play a role in this complex journey.

Absorption: Getting the Drug In

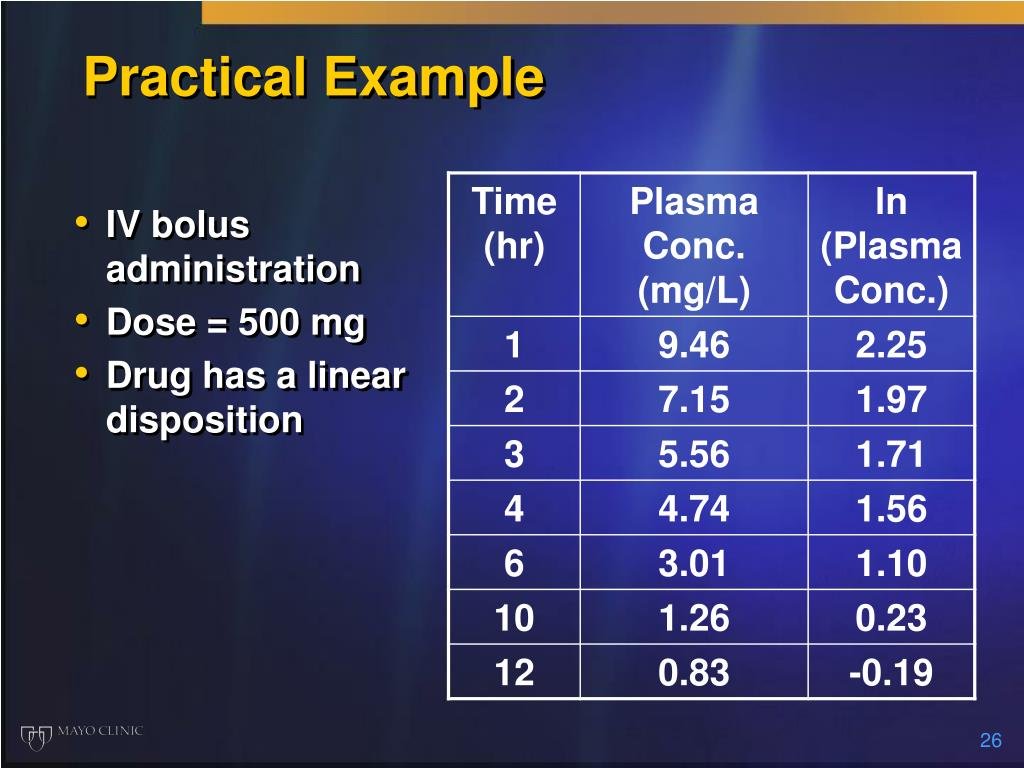

Absorption is the crucial first step where a drug moves from its administration site (like your stomach or a muscle injection) into your systemic circulation – your bloodstream. If a drug is given intravenously (IV) or intra-arterially, it bypasses this step entirely, going straight into the blood. For other routes, sufficient absorption is key; too little, and the drug won't work. Too much, or too fast, and you risk toxicity.

A critical concept here is bioavailability: the fraction of an administered dose that actually makes it into your systemic circulation, unchanged and ready to act.

What Influences Oral Absorption?

Taking a pill seems simple, but getting that drug into your system is a finely tuned process:

- The Drug Itself (Physicochemical Properties):

- Lipid Solubility: Drugs that dissolve well in fat, like diazepam, tend to cross cell membranes (which are fatty) much more easily.

- Ionization State: Cell membranes are generally happier letting non-ionized (uncharged) molecules pass. Weak acids (like aspirin) absorb better in the stomach's acidic environment where they are less ionized, while weak bases (like propranolol) prefer the more alkaline intestines.

- Molecular Size: Smaller molecules can diffuse across membranes with greater ease.

- Your Gut's Environment (Gastrointestinal Physiology):

- pH Gradient: Your stomach is highly acidic (pH 1-3), while your intestines are more neutral (pH 6-7.5). This difference impacts a drug's ionization state and, therefore, its absorption.

- Food's Role: Eating can slow stomach emptying, dilute the drug, or even bind to it, preventing absorption (e.g., tetracyclines bind with calcium in dairy).

- Motility/Transit Time: If your gut moves too fast (diarrhea), there's less time for absorption. If it's too slow, contact time increases, but it can also delay the drug's effect.

- How the Drug is Packaged (Formulation and Delivery Systems):

- Disintegration: A tablet must first break apart.

- Coatings: Enteric coatings protect drugs that would otherwise be destroyed by stomach acid, ensuring they dissolve in the intestines.

- Release Type: Immediate-release (IR) formulations release the drug quickly, while extended-release (ER) versions spread absorption over many hours.

The First-Pass Problem

A significant hurdle for many oral drugs is First-Pass Metabolism. This occurs primarily in the liver, but also in the gut wall and by intestinal microflora. As the drug is absorbed from the GI tract, it travels via the portal vein directly to the liver before reaching the rest of the body. The liver, a metabolic powerhouse, can extensively break down the drug, dramatically reducing its bioavailability. Nitroglycerin, for example, is almost completely destroyed by first-pass metabolism if swallowed, which is why it's administered sublingually (under the tongue) or transdermally to bypass the liver initially.

Distribution: Where the Drug Travels

Once a drug enters the bloodstream, distribution is its journey from the blood into the interstitial fluids (between cells) and then into the cells themselves, where it can finally exert its pharmacological effect. This spread depends on a few key factors:

- Blood Flow: Organs with high blood flow (brain, heart, liver, kidneys) receive drugs more quickly than those with lower flow (fat, muscle).

- Drug Properties: Lipid-soluble drugs can easily cross cell membranes and distribute widely.

- Volume of Distribution (Vd): This isn't a literal volume, but a theoretical concept that relates the total amount of drug in the body to its concentration in the plasma.

- A low Vd (around 3-5 liters, similar to plasma volume) means the drug mostly stays in the bloodstream (e.g., heparin).

- A moderate Vd (12-20 liters) indicates distribution into the extracellular fluid (e.g., mannitol).

- A high Vd (over 40 liters) suggests the drug has extensively penetrated tissues, sometimes accumulating in specific compartments (e.g., digoxin, which has a Vd often exceeding 400 liters, indicating strong tissue binding).

- Plasma Protein Binding: Many drugs reversibly bind to proteins in the blood, primarily albumin. Crucially, only the free (unbound) drug is pharmacologically active. If two highly protein-bound drugs (like warfarin and sulfonamides) compete for the same binding sites, the free concentration of one or both can transiently increase, leading to a stronger effect or even toxicity. Conditions like liver disease, which cause low albumin levels (hypoalbuminemia), can also increase the free drug fraction.

- Special Barriers:

- Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB): This highly selective barrier protects the brain, allowing only very lipophilic drugs or those with specific active transport systems (e.g., levodopa) to enter the Central Nervous System.

- Placenta: While not as restrictive as the BBB, the placenta allows many drugs to cross from mother to fetus, especially lipophilic, non-ionized ones. This necessitates extreme caution when prescribing medications during pregnancy.

Metabolism: Changing the Drug

Metabolism, also known as biotransformation, is the chemical modification of drug molecules within the body. Its primary goal is usually to make drugs more polar (water-soluble) so they can be more easily excreted. While the liver is the main metabolic hub, other sites like the gut wall, lungs, and kidneys also contribute.

Often, metabolism inactivates a drug. However, some drugs are prodrugs (e.g., enalapril), which are inactive until metabolized into their active forms. Conversely, metabolism can sometimes create toxic intermediates, as seen with acetaminophen, where a small fraction is metabolized into a harmful compound called NAPQI (which is normally detoxified by glutathione).

Metabolic reactions are typically divided into two phases:

- Phase I (Functionalization Reactions): These reactions introduce or expose polar functional groups (like hydroxyl groups) and include oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis. The most critical players here are the Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes, a family of liver enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, CYP2C19) responsible for metabolizing the vast majority of drugs.

- Drug Interactions: Clinically significant interactions often arise from changes in CYP450 activity. Some drugs (like rifampin) can induce these enzymes, speeding up the metabolism of other drugs and reducing their effectiveness (e.g., making oral contraceptives less effective). Other drugs (like ketoconazole) can inhibit these enzymes, slowing down metabolism and increasing the risk of toxicity from other medications.

- Phase II (Conjugation Reactions): These reactions involve attaching a larger, highly polar endogenous molecule (like glucuronic acid, sulfate, or glutathione) to the drug or its Phase I metabolite. This makes the compound even more water-soluble and ready for excretion. Examples include glucuronidation (e.g., morphine-6-glucuronide) and sulfation (e.g., acetaminophen). Genetic variations (polymorphisms) in enzymes like N-acetyltransferase (NAT2), which performs acetylation (e.g., for isoniazid), can lead to significant individual differences in drug handling.

- Genetic Polymorphisms: These variations in metabolic enzymes (like CYP2D6, NAT2, TPMT) explain why different people respond so differently to the same dose of a drug. A "poor metabolizer" might experience severe side effects at a standard dose, while an "ultrarapid metabolizer" might get no benefit at all (e.g., codeine's pain relief depends on its conversion to morphine by CYP2D6).

- Clinical Relevance: Patients with liver damage (cirrhosis, hepatitis) have reduced metabolic capacity, requiring lower doses of many drugs to avoid toxicity. Heart failure can also impair metabolism by reducing blood flow to the liver.

Excretion: Getting the Drug Out

Excretion is the final act of the ADME play, where the drug and its metabolites are removed from the body. This process is vital for terminating a drug's action and preventing its accumulation to toxic levels. The kidneys are the primary route, but the liver (via bile), lungs, and even minor routes like sweat, saliva, and breast milk also play a part.

Renal Excretion: The Kidney's Role

The kidneys process drugs through three main mechanisms:

- Glomerular Filtration: Small, unbound drug molecules are filtered from the blood into the kidney tubules. Drugs bound to plasma proteins are generally too large to be filtered.

- Tubular Secretion: Active transport systems in the proximal tubule (e.g., OAT for organic acids, OCT for organic bases) actively pump drugs and metabolites from the blood into the tubular fluid. For instance, penicillin is extensively secreted this way.

- Tubular Reabsorption: As the fluid moves through the tubules, lipid-soluble or non-ionized drugs can passively diffuse back into the bloodstream. This means acidic or alkaline urine can be used to "ion trap" drugs during an overdose – making them ionized and unable to reabsorb, thus speeding up their excretion.

- Clearance (CL): This is a quantitative measure of the volume of plasma from which a substance is completely removed per unit time. It's a critical parameter for determining maintenance doses.

- Half-Life (t½): The drug's half-life – the time it takes for the plasma concentration of a drug to reduce by half – is directly influenced by its volume of distribution (Vd) and inversely by its clearance (CL). The formula is t½ = (0.693 × Vd) / CL. Drugs with a short half-life (like nitroglycerin, 1-4 minutes) disappear quickly and need frequent dosing or continuous infusion. Explore second-generation cephalosporins, a class of antibiotics, often have their dosing frequency determined by their half-life and renal clearance.

Hepatobiliary Excretion: The Liver's Second Exit

The liver doesn't just metabolize; it also excretes some drugs and their metabolites directly into the bile. This bile then enters the intestines. Some conjugated metabolites, particularly glucuronides, can be "deconjugated" by intestinal bacteria, allowing the parent drug to be reabsorbed into the bloodstream. This process, known as enterohepatic recycling, can significantly prolong a drug's half-life (e.g., some oral contraceptives).

Pulmonary and Other Minor Routes

Volatile drugs, such as general anesthetics and ethanol, are primarily exhaled by the lungs. Drugs can also diffuse into breast milk, posing potential risks to nursing infants (e.g., diazepam, codeine).

Clinical Pharmacokinetics: Translating Science into Safe Dosing

Clinical pharmacokinetics takes these ADME principles and applies them directly to patient care. The goal is to design dosing regimens that keep drug concentrations within a specific therapeutic window – a range where the drug is effective without causing undue toxicity.

Tailoring Doses: Loading and Maintenance

- Loading Doses: When a rapid therapeutic effect is needed, a larger initial dose is given to quickly achieve the desired plasma drug concentration. The formula for a loading dose often involves the Volume of Distribution (Vd) and the target concentration. Digoxin is a classic example where a loading dose might be used.

- Maintenance Doses: Once target levels are achieved, maintenance doses are given regularly (or as a continuous infusion) to replace the drug lost through elimination and keep the plasma concentration stable within the therapeutic window. This dose is often calculated using the drug's clearance (CL) and the desired concentration.

- Steady-State: After multiple doses, the body eventually reaches a point where the rate of drug administration equals the rate of drug elimination. This is called steady-state, and drug concentrations fluctuate predictably around an average level. It typically takes about 4-5 half-lives for a drug to reach steady-state. Drugs with short half-lives (like nitroglycerin) reach steady-state quickly, while those with very long half-lives (e.g., amiodarone, with a half-life of 20-50 days) can take weeks or even months.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM): Keeping Watch

For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (where the difference between an effective dose and a toxic dose is small), Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) is essential. This involves measuring actual plasma drug levels in patients to guide dosage adjustments. Warfarin, digoxin, lithium, and certain anticonvulsants are prime examples where TDM helps ensure safe and effective concentrations, preventing both under-dosing (therapeutic failure) and over-dosing (toxicity).

Beyond Basic Physiology: Factors That Influence ADME

While the core ADME processes are universal, many individual and disease-related factors can profoundly alter a drug's journey through the body, necessitating personalized dosing.

Age: From Infants to Seniors

- Neonates and Infants: Their bodies are still developing. They often have immature hepatic enzymes (affecting metabolism), lower glomerular filtration rates (GFR, affecting excretion), and different body water compositions. This means many drugs need significantly lower doses or different dosing intervals in this population.

- Elderly Patients: With age, renal function naturally declines, hepatic metabolism can be altered, total body water decreases, and fat content may increase. Coupled with potential polypharmacy (taking multiple medications), this makes the elderly particularly vulnerable to altered drug effects and adverse events, demanding careful dosing adjustments.

Pathophysiological States: When Disease Changes Everything

- Kidney Disease: Impaired kidney function (reduced GFR or tubular activity) hinders drug excretion, leading to accumulation and toxicity for renally cleared drugs (e.g., aminoglycosides, vancomycin). Dosing adjustments based on estimated GFR are crucial.

- Liver Disease: Conditions like cirrhosis or hepatitis reduce the liver's metabolic capacity, increasing the risk of toxicity for hepatically metabolized drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines, opioids).

- Heart Failure: Decreased cardiac output can reduce blood flow to organs like the liver and kidneys, impairing both metabolism and excretion. This often necessitates lower doses.

Pharmacogenetics: Your Genes, Your Drugs

Genetic polymorphisms (variations) in metabolic enzymes (e.g., CYP2D6, NAT2, TPMT) or even drug transporters lead to significant inter-individual variability in how people handle drugs. This explains why:

- Some individuals get little to no effect from a standard dose of codeine (if they have a non-functional CYP2D6 to convert it to morphine).

- Others might experience severe side effects from isoniazid (if they are "slow acetylators" due to NAT2 variations).

- TPMT polymorphisms affect how quickly mercaptopurine is metabolized, guiding dosing to prevent severe bone marrow suppression in cancer patients.

This burgeoning field of pharmacogenetics is moving us towards more personalized medicine, where drug choices and doses are tailored to an individual's genetic makeup.

Practical Examples: ADME in Action

Let's look at how these concepts play out with common medications:

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol):

- Absorption: Rapidly absorbed from the GI tract.

- Metabolism: Primarily in the liver through glucuronidation and sulfation, making it easy to excrete. A small, usually harmless, fraction forms the toxic metabolite NAPQI, which is quickly detoxified by glutathione.

- Excretion: Conjugated metabolites are excreted renally.

- Clinical Point: In overdose, glutathione stores are overwhelmed, leading to NAPQI accumulation and severe hepatotoxicity.

- Warfarin (Coumadin):

- Absorption: High oral bioavailability.

- Distribution: Highly bound to plasma proteins (~99%).

- Metabolism: Primarily by CYP2C9 in the liver. Genetic polymorphisms in CYP2C9 (and VKORC1) significantly affect individual dose requirements.

- Excretion: Metabolites excreted renally.

- Clinical Point: Extremely narrow therapeutic index. Its high protein binding means interactions with other protein-bound drugs can be critical. CYP2C9 interactions (inhibitors like fluconazole, inducers like rifampin) can dramatically alter its effects, requiring careful Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) via INR (International Normalized Ratio).

- Beta-Lactam Antibiotics (e.g., Penicillin G):

- Absorption: Many oral forms are partially inactivated by gastric acid.

- Metabolism: Minimal hepatic metabolism for many.

- Excretion: Primarily via rapid renal tubular secretion.

- Clinical Point: Their short half-life often necessitates frequent dosing. Probenecid can be co-administered to inhibit tubular secretion, prolonging penicillin's half-life and increasing its effectiveness.

- Digoxin:

- Absorption: Variable GI absorption.

- Distribution: Has a very large Vd, indicating extensive tissue binding.

- Metabolism: Minimal hepatic metabolism; some degradation by gut flora (antibiotics can sometimes increase digoxin levels by killing these bacteria).

- Excretion: Primarily renal clearance of the unchanged drug.

- Clinical Point: Impaired renal function significantly extends its half-life and can lead to toxicity. Narrow therapeutic index requires TDM.

- Levothyroxine (Synthroid):

- Absorption: Incomplete absorption, influenced by food and antacids.

- Distribution: Highly bound to plasma proteins.

- Metabolism: Hepatic deiodination.

- Excretion: Biliary excretion with some enterohepatic circulation.

- Clinical Point: Very long half-life (about 7 days) means it takes several weeks to reach steady-state after a dose change, and plasma monitoring is typically done only after this period.

Optimizing Therapy: Leveraging ADME for Better Patient Outcomes

The sophisticated understanding of ADME isn't just academic; it's the foundation of rational drug therapy.

- Precise Dosing in Renal Failure: For drugs primarily cleared by the kidneys (like aminoglycosides or vancomycin), knowing a patient's kidney function allows clinicians to adjust doses downwards, preventing toxic accumulation.

- Managing Drug Interactions: Understanding which drugs are CYP450 enzyme inducers (e.g., rifampin) or inhibitors (e.g., fluconazole) is crucial. This knowledge helps healthcare providers anticipate and prevent drug interactions that could lead to therapeutic failure (e.g., oral contraceptive failure) or severe toxicity (e.g., increased phenytoin levels when co-administered with fluconazole).

- Pediatric and Geriatric Dosing: Specialized dosage formulations and guidelines exist for children and the elderly, accounting for their unique physiological differences in ADME processes.

- Innovations in Drug Delivery: Researchers are constantly developing new drug delivery systems – like nano-carriers or liposomal encapsulation (e.g., liposomal amphotericin B to reduce kidney toxicity) – that strategically exploit ADME pathways for targeted release, improved efficacy, and reduced side effects.

Ultimately, a thorough grasp of ADME processes is not just fundamental to pharmacology; it's indispensable in clinical practice. It empowers healthcare professionals to customize therapies, ensuring maximum efficacy, paramount safety, and overall patient satisfaction. By considering individual variations, existing disease states, and the potential for drug interactions, we can truly deliver on the promise of personalized and effective medicine.